The Wa Heartland

Can the spectacular scenery of the Wa-controlled regions of Burma draw enough tourists to break the hold of the only cash crop that can cling to the steep, arid slopes – the opium poppy?

Armin Schoch

The Chinese border officials saluted our convoy of 12 Chinese 4WD cars as we slowly drove across the bridge over the Namkam River, which separates China from the Wa State, Little did I know that four days later I would have to wade hip-deep through the turbid river to get back to China. Despite the border hiccups, my five-day stay in this part of Burma, officially called Special Region 2, was a rewarding experience. In face, it fulfilled my long-held dream of getting Into this part of the world where few foreigners had entered. My expedition into the Wa State was made possible by a Chinese friend with a strong vocation for development projects in remote minority-populated areas of Yunnan and Tibet. He invited me to join him and a delegation of like-minded persons in a convoy of cars from Kunming. The invitation was issued by the highest Wa authority. The stated objective was for us to come and see the situation as it really is, with our own eyes.

And, in view of the Wa leadership’s declaration that is will eradicate poppy cultivation by 2005, they wanted us to make recommendations on how to develop substitute means of income. In particular, they wanted to explore the possibilities of generating quick revenues through tourism. Fittingly, the trip was named the “2004 Golden Triangle Tourism Resource Expedition”. Our delegation included representatives from two reputed non-governmental organisations operating in remote China, businessmen, journalists and photographers from Xinzhoukan Magazine (the largest publication in mainland China), Ming Pao (the second largest Chinese-language newspaper in Hong Kong), and a famous Chinese outdoor/adventure travel magazine. Kunming’s 4WD enthusiasts provided transport for our delegation. Except for one person each from Hong Kong, Manchuria, France and Switzerland (myself), all participants were Chinese.

Pang Sang

We were met at the border by a Wa TV crew and a high-ranking Wa State government official. A short drive of two kilometres brought us into the Wa capital of Pang Sang, and to the Maxxin Hotel, where the same high-ranking official delivered a welcome speech in Chinese. I was surprised to learn that Chinese is widely spoken in the Wa State, and that the people generally do not speak Burmese at all. We were disappointed, however, in the propagandistic and uninspiring tone of the speech.

Discovering the town on foot sounded like a welcome change of itinerary, and we all set out in different directions. A few persons walked right into the army camp in town, where they talked to the soldiers. We were allowed to take pictures at will. I saw many brand new 4WD cars and limousines. On the streets and at the central market, where most of the goods are imported from either China or Thailand, we found ethnic people in a variety of different costumes, along with mostly Burmese and Indian-Burmese traders. Muslims and Buddhist monks.

But I was saddened to see many child beggars in torn and dirty clothes, and prostitution is also rampant in Pang Sang, which has a casino and an entertainment complex. I chose to visit a large stupa resembling the Shwedagon Pagoda in Yangon just outside of Pang Sang. This stupa, allegedly Burma’s fourth highest and covered with 27 bricks of gold weighing 70 kgs each, was built only a few years ago. It’s height of 135 metres symbolises Burma’s 135 minorities.

Later, over good food and plenty of rice wine at a local restaurant, we started to get acquainted with our Wa hosts.

After a comfortable night at the Maxxin Hotel, we set out for our first encounter with rural Wa life. The asphalt road vanished as we left Pang Sang and we drove up into the surrounding mountains on a road that was partly dirt track and partly paved with crudely cut stones. Driving in the direction of Mong Pauk, approximately 40 kms southwest of Pang Sang, we were struck by how dry the land everywhere around us looked and were told by our hosts that indeed it is extremely difficult to grow rice, fruit or other crops on the arid soil in the North Wa State. Our hosts explained that the 100,000 Wa people who had moved south to settle along Thailand’s northern border has met there with much better agricultural conditions.

Arriving at Mong Pauk, we visited a local orphanage/school for 400 children ranging from 4 to 13 years. On our arrival, the children lined both sides of the road leading up to the school waving flags, while older boys beat their drums in greeting. The orphanage/School, seemingly funded by Mr. Pau Yu Chang, the chairman of the United Wa State Army (UWSA), looked clean and well managed, although the headmaster explained to us that adequate hygiene was still lacking. After the children sang a few songs for us, we had the opportunity to talk to them. We were told over and over again that their parents had died of illnesses, an answer that many of us felt was not quite accurate, given the recent military history of the UWSA. We returned to Pang Sang later that day.

The next day, we set out for a six-hour drive to Long Tan, a strategic military headquarters of the UWSA, north of Pang Sang. It was clear to us that not many visitors had ever been allowed to travel this far into the Wa hills and hence it was with great anticipation that we looked forward to what the day would bring.

Pau Yu Chang… No poppy cultivation by 2005

This golden pagoda near Pang Sang is covered with 27 bricks of gold.

Uniformed children greet visitors to an orphanage in Mong Pauk.

Two Wa women explore a cultivated poppy field near their village.

Poppy Country

Leaving Pang Sang, the road began climbing immediately and we soon reached altitudes of over 1,500 metres. Once again, we realised that, given the steep mountain slopes, arid soil and lack of water and irrigation systems, it would be extremely difficult to successfully develop any crops in sufficient quantity substitute for poppy cultivation.

We did not see any rice fields or terraces, only a few rubber tree plantations. Near the ruins of and old stupa we made our first stop, and discovered a poppy field nearby. The bulbs of the plants showed clear signs of incisions and we encountered several women in the fields looking after the hardy plants. The harvest being over for many weeks, the poppy plants were all yellow and dry, but still alive. In the villages, some of which struck us as being unusually large, we saw clear signs of poverty. It became abundantly obvious that eking out a living in these remote and isolated hills is very hard indeed.

At Banno village, we had lunch and realised that if most of the food had not been brought along from Pang Sang, the locally available food would have a few upset stomachs. Shortly before arriving at the military headquarters of Long Tan, the air became crisp and we were travelling through spectacular mountain scenery at an altitude above 2,000 metres. There, we suddenly found ourselves in the midst of poppy fields as far as the eye could see.

Driving into Long Tan, at an altitude of 2,170 metres, we noticed two local men with their feet chained together being marched to jail by UWSA soldiers. Apparently the two men had been arrested for drug offences.

After we arrived at the UWSA headquarters and were taken to our living quarters, we were invited to visit Long Tan Lake, a short walk of 20 minutes. The lake surrounded by high rees and wild looking mountains, was a very beautiful sight indeed. The local food served for dinner was extremely basic, but that was more than compensated for by the warmth and genuine hospitality of our hosts. At some point, as an impromptu bonfire was started outside, what had begun as a performance of dances and songs to welcome our delegation was transformed into a party for everyone present. Hosts and visitors alike continued to dance and sing late into the night.

The next morning our delegation was received by Mr. Pau Yu Chang, who reiterated in a frank and direct manner that the Wa leadership intends to eradicate poppy cultivation and stop timber logging by 2005, as they had realised that the Wa would otherwise destroy their own future. But Mr. Pau mad no secret of the fact that although the Wa leadership is appealing for international help, it would be extremely difficult to sufficiently develop substitute economies and tourism to successfully feed the Wa people. Chairman Pau explained that the aid received from the government in the wake of the ceasefire agreement the We reached with Rangoon was insufficient and not suitable for the prevailing conditions in the Wa hills. He said that the government should allow more Wa people to move south towards the Thai border.

Then it was time to drive back to Pang Sang. Once again we drove through the poppy fields amidst the spectacular mountain scenery–as extremely beautiful as it is unyielding to agricultural pursuits. Our now trained eyes discovered poppy fields near almost every village that we passed on our way down to Pang Sang.

Ethnic people are widely seen in Pang Sang.

The author with a young Wa official.

A Thai-style tuk-tuk in Pang Sang.

Four different insignias worn by Wa police and soldiers.

A small opening

After another comfortable night in Pang Sang, we said goodbye to our Wa hosts and headed for the Chinese border, only to find out that the middleman from Yunnan who had arranged for our crossing into the Wa State had not made any arrangements with the Chinese officials for our return to China. Several hours of negotiations ensued, and after intervention from Mr. Li Zu Ru, the UWSA vice-chairman, the Chinese officials agreed to readmit the cars and all Chinese delegation members holding proper Chinese ID cards. The officials steadfastly refused, however, to let those considered foreigners, which included the Hong Kong native, cross back into China, on the grounds that this was not an international border point, and because the middleman had omitted to declare the foreign delegation members on the list he had previously provided.

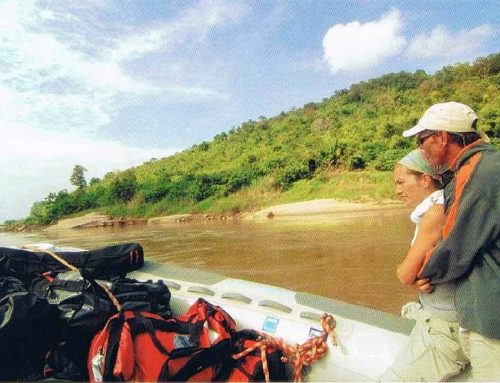

At long last, our hosts decided to send a car across the river to China while we moved downriver on the Wa side. Sitting on the riverbank and waiting for the car to appear on the Chinese side, the four of us had ample time to reflect on the consequences we might face if ever the Chinese authorities caught us at what we were about to do. Finally, the car arrived on the other side and, clutching our few belongings, we painstakingly waded through hip-deep water across the river and back into China. Once safely in the car and on my way back to Kunming. I reflected on the experiences and impressions I had gained during the last five days in the Wa State. It seems obvious to me that a strong Wa leadership (as is in place) is necessary to trace a way out of poppy cultivation and towards development of a real economy.

The Wa leadership is aware that this will be an extremely difficult undertaking–given the extreme limitations to successfully develop agriculture and tourism–and open questions remain as to what will happen if success is not met within a reasonable time period.

The fear and danger is that in the absence of a substitute income, the Wa will continue (or revert to) poppy cultivation, most likely in a more hidden form, to sustain themselves financially. On the other hand, the renewed tourism interest and the ongoing drive to develop the tourism potential in the north part of Thailand and beyond into neighbouring Laos and Burma might indeed present a small opening for the Wa, particularly if they can convince China and Burma to facilitate international access to the Wa State. One has to realise, however, that Chairman Pau is probably right when he says that opening the Wa State up to tourism will not, in terms of income for the average villager, provide a substitute to poppy cultivation.

Tourism can certainly help to end the isolation of the Wa from the rest of Burma and to facilitate the development of other aspects of society, such as communications, educational and healthcare systems, but more is needed in order for the people of the Wa to make a clean break with the past. Clearly it is in the interests of Burma’s closest neighbours to provide assistance and resources to the Wa and to allow migration when feasible. The fate of the Wa people must be of concern to the governments and the peoples of Burma. Thailand and China, as they will not only largely define, directly or indirectly, the success of any positive outcome, but will otherwise have to bear the consequences of their complacency

Click here to read the original article.